Engaging high school students with America’s complicated history

Published 4:00 pm Friday, February 3, 2023

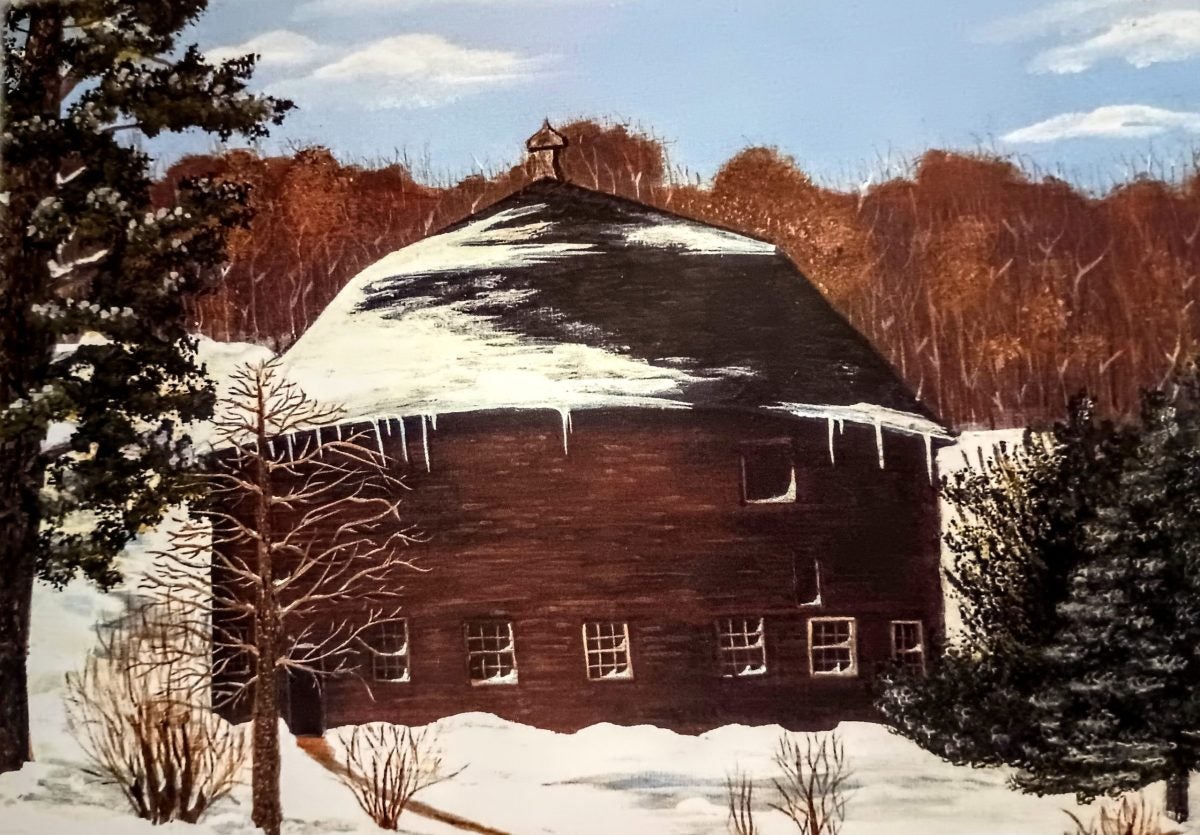

- Photo cutline: DeWitt-King Barn in Vernon County, Wisconsin. (Painting by Patsy Alderson)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Sara June Jo-Sæbo

The Daily Yonder

Patsy Alderson preserves Wisconsin’s rural life by collecting stories and through her paintings of its landscapes and structures. Her husband, Kevin, joined her conservation efforts when he retired from teaching public school. Together, they are lifelong educators, and Kevin’s 30-year tenure teaching middle- and high-school history add to their credentials as stewards for their region’s history. Committed to uncovering and safeguarding the racial and ethnic diversity of rural Wisconsin, the Aldersons offer educational community programs to ensure that our inheritance with diverse American experiences isn’t lost.

Because he was teaching American history in rural school districts, I wanted to talk to Kevin about ways he engaged high school students in the classroom and to get his opinion about how teaching history has changed over the last 40 years. I also wanted to hear about how country schools and school consolidation affected rural students and racial diversity. His answer might surprise you.

Sara June, Daily Yonder: Where did you teach school, what subjects and grades, and for how many years?

Kevin Alderson: I taught at Wautoma High School in Wisconsin for four years and then most of my career was at Cashton, Wisconsin and I was there 29 years. I was a social studies teacher. I taught juniors and seniors.

DY: In the book that you and Patsy wrote in 2010, “Barns Without Corners”, you say that it’s important that history curriculums emphasize local and regional history. Do public schools teach local and regional history today? What impact does learning local and regional history have?

KA: Toward the end of my career (early 2000’s), there was a really strong movement toward standardized education. When I graduated from college back in the 70’s, we were taught to spend more time on primary sources and outside sources and use the textbook as a reference rather than an “historical bible”. One thing that I think has been a mistake – unless I’m inaccurate – is that standardized testing has pushed everybody back into textbooks… and worksheets (homework) that line up with standardized testing. My point of view is that [standardized curriculum and testing] took a lot of what I liked to teach and what I thought was important [in history curriculum] out of the equation.

What I feel is lost when you teach the standardized curriculum in history is this: history is all about connection. Teachers have to figure out a way in which students can connect to what’s being taught. In my experience, to make the connection for my students, I started with their family history and then carried that on into local history. Then, when you’re talking about, for example, immigration or the Civil War… connections can be made for the student through their family and their local history.

DY: As a history teacher, what did you observe in the classroom when students learned local history?

KA: While my approach to teaching family and local history didn’t reach every student, for many of them, being able to connect national and world events with their families and local events – and seeing that they (the students) were part of the story – was the best method. It was about making a personal connection to that history.

DY: Much of American history involves colonizing this continent through the use of impoverished Europeans and enslaved Africans. Our history also involves the persecution of Indigenous people. Does teaching about these traumatic experiences harm students?

KA: I accept the argument that we may not be responsible for what was done in the past because we weren’t alive then, but we are responsible for learning the truth about what happened. We fail when we don’t admit that this history happened and we fail when we don’t know the truth about what happened. [When we don’t learn the truth of our history] it’s dangerous to the country because we’re living a myth; we’re living with lies. Even though I don’t think teachers intentionally teach “lies”, if you don’t do your own research and dig deeper and use primary resources, you perpetuate histories that are inaccurate year after year and then a “lie” becomes a “truth”. If you’re truly trying to teach history – difficult history – you have to teach the greatness, the good, the bad, and the ugly. Unfortunately, the systemic tendency is to teach the great and the good and whitewash, or erase and ignore, the bad and the ugly. And there are a lot of people who have paid a heavy price for being overlooked.

DY: Most people don’t know that Wisconsin has a substantial history of successful Black farmers who were also our earliest American pioneers. Tell me how you were exposed to Wisconsin’s African-American history in your own childhood.

KA: I was not exposed to Wisconsin’s rural African-American history as a child. I remember a lot of emphasis on the textbooks but I knew nothing of Cheyenne Valley (the recent name that was applied to this particular settlement of Wisconsin’s Indigenous, African-American, and European-American Pioneer community in Vernon County) which is within 15 miles from us [here in La Farge]. I’ve talked to some of the people who went to Hillsboro (Wisconsin) schools and they didn’t know much about the history of this settlement which is only 5 miles from them. Most of the rural Black history I’ve learned has been since I retired from teaching.

DY: As an adult, what motivated you to help to preserve Wisconsin’s African-American and Indigenous history?

KA: This awareness of rural Black history in Wisconsin came to us through our interest in round barns. My wife, Patsy, is an artist who paints structures and landscapes. Of course, here in Vernon County (Wisconsin) we have the most round barns, as far as I know, in the nation. She began to make paintings of all the round barns that remained. I began researching the barns and, built upon what the Vernon County Historical Society had compiled, discovered the history of Wisconsin’s Black settlements. [I discovered that] Alga Shivers was a leading designer, engineer, and builder for many of the regions round barns. So, Patsy made these art note cards with her paintings and I wrote a brief history on the back [of the cards]. Then we decided to organize it into a book about the builders of the round barns and include the history of Alga Shivers who was the son of the formerly enslaved American, Thomas Shivers.

DY: So you hadn’t heard of the Shivers family or heard of Black history in Vernon County before?

KA: No, I had heard of it. I met Alga Shivers when I was a child. My dad was part of the Caucasian settlers in the town of Forest; he lived on Burr Ridge. Wesley Barton was one of the earliest settlers in the town of Forest. His son, Cornelius, became one of the first – if not the first – Black postmasters in the nation. Even though my dad was not a contemporary of Wesley Barton, my dad lived ¾ of a mile from Barton’s corner and attended the area’s integrated school called Burr School. There were several country schools in the Cheyenne area that were racially integrated back then.

DY: What conditions made it possible for Black Americans to live in rural Wisconsin in the 1800s?

KA: The availability of land; coming to a new state where the laws didn’t limit freedoms for Free Blacks; and the pressures to escape Southeastern states.

I would say the movement of Free People of Color out of the Southern states was directly linked to the Nat Turner Rebellion [1831]. The movement into the Northwest Territory (Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Northeast Minnesota) was due to the availability of land. The movement to Wisconsin was related to the Fugitive Slave Law and because Wisconsin wasn’t a very established state. We didn’t become a state until 1848 – and the Cheyenne Valley settlement was established in 1854 and the town of Forest was established in 1855.

As more and more laws were passed in Southern states against People of Color – being taxed for being Black; limiting freedom to travel; denying people the freedom to learn to read and write; not being able to own guns or testify in court; denied the right to vote – they moved inland into the Northwest Territory. The 1787 Ordinance of the Northwest Territory mandated that slavery was illegal. And (when) the Northwest Territory was opened up, (settlement) started in Ohio where you could buy land for $1.25 per acre. As soon as Ohio became a state, their legislature started passing laws restricting free People of Color. So many moved from Ohio to Indiana; the Roberts Settlement, a multi-racial settlement. But in 1850, with the passing of the Fugitive Slave Law, Indiana was far enough South that they were still being threatened by slave catchers – even if you had papers saying you were free.

DY: Getting into the 1900’s what made it difficult for Wisconsin’s rural Black communities to remain in Southwest Wisconsin?

KA: Interestingly enough, a lot of the settlement faded away with the elimination of country schools. Instead of having your own little school and settlement – which were integrated Black, White and Native American – as soon as they were closing those schools as early as the 40’s and 50’s, they bussed those students to towns and any time new folks are brought into an environment – even from the country to the town – it often created an “us and them” situation. I think the community lost some its identity when the country schools were brought into bigger districts.

Another factor is that our farming is very limited. We’re in the Driftless area where we typically had 80 acre, 100 acre farms that were very sustainable; small herds and small crops grown to feed your livestock and your family. When [family farm] operations got bigger, the smaller farms dissolved throughout all of Wisconsin. Part of the movement of Wisconsin’s rural People of Color was a part of this progression from rural to urban.

Descendants of Black people who could pass as white, remained in rural areas. Descendants with darker skin color moved to cities like Milwaukee and Madison. In the words of Alga Shivers, those who could “blend in” tended to remain. But some of the African-American descendants with darker skin color – like Alga Shivers – did remain.

And there was a KKK presence in Vernon County in the 1920’s, with the Klan president living in Viroqua (Vernon County’s county seat). I don’t know if there was enough pressure coming from the Klan to make people leave the area; it certainly didn’t help.

DY: How can educators teach this complicated story of American history?

KA: Intentionally or unintentionally, racism is systemic. There’s a conflict right now between recognizing the truth [of our American history with racism] and suppressing the truth. And how does an individual, or society, or nation move forward into something better if you don’t recognize the mistakes that have been made? Especially if you continue to perpetuate those mistakes? [Without the truth] you can’t grow as a human being and you can’t grow as a society. We short-circuit ourselves from reaching our own potential.

We don’t have to attack our ancestors because it was a different day and a different age. You can teach what happened [in American history] without passing judgment… There are certain things in our history that were evil. Period. But there’s [also] a force of survival: looking for land and looking out for their families.

It’s amazing to me the things I didn’t know [about American history] even when I was teaching. Much of what we experience in America can go back to The Doctrine of Discovery (15th Century Papal decree authorizing the deadly conquest of non-Christian people and lands). Manifest Destiny. I used to teach “Manifest Destiny” without any reservation as something that made America great. Depending on how you define “great” because a lot of “greatness” is equated with money and power – and Manifest Destiny, in fact, did help make America “great” monetarily and powerfully. But it didn’t make us “great” morally.

DY: As a descendant of European settlers, why is it important to you to preserve the history of Black Americans who settled your home state of Wisconsin?

KA: Because the complete truth matters. I want to know the complete truth of all facets of American history. And, in fact, it goes beyond preservation. Most people are probably unaware of Black American settlement in Wisconsin during pioneer days. That is especially the case in rural areas such as the Cheyenne Settlement in the Town of Forest in Vernon County. Much of the history is unknown by most people and some of what has been recorded is inaccurate or incomplete. I am fascinated that, at least for a while, the pioneers of the Town of Forest seemed to have overcome racial prejudice and worked together as a community. History cannot be preserved if people don’t know it in the first place.

This story was originally published in the Daily Yonder. For more rural reporting and small-town stories visit dailyyonder.com.