Fort Knox honors heroic battlefield actions of WWII Black tank soldier

Published 2:00 pm Saturday, February 27, 2021

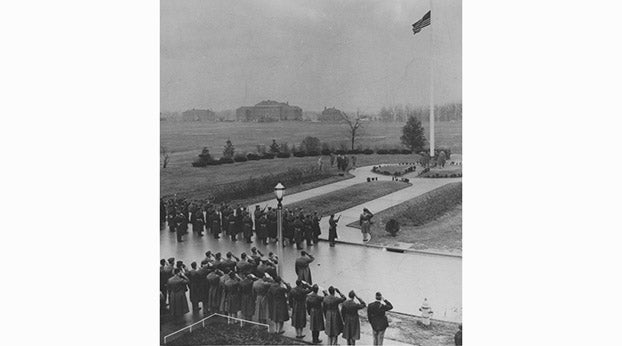

- A ceremony honoring World War II hero Robert Brooks, who was a Black tank soldier. (Fort Knox photo)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

FORT KNOX, Ky. — Hundreds of thousands have stood on Brooks Field in celebration of something over the years.

Whether it’s the 10,000-plus cadets and their families relishing their graduation from Cadet Summer Training, troops marching in precise step during a pass in review with their new commander at the helm, or countless festive goers from on and off-post gathering to mark holidays together, Brooks is the place to gather.

Listed as the first American tanker killed in combat during World War II, Robert Brooks is the appropriate hero to bear the field’s name.

“We memorialize things of Fort Knox to heroes or people who are significant to our history,” said Matthew Rector, historic preservation specialist at the Fort Knox Cultural Resources Office. “Robert is one of our heroes.”

A plaque that sits in concrete in front of the parade field reads, “Dedicated 23 December 1941 in memory of Private Robert H. Brooks 8 October 1915 – 8 December 1941, Company D, 192nd Tank Battalion, Kentucky Army National Guard. Killed in action at Clark Field, Luzon Philippines.

A lesser-known display case sits in Fort Knox Garrison Headquarters, against a wall near the stairs. The onus for it came from former Garrison Senior Enlisted Advisor Command Sgt. Maj. Marcus Robinson sometime between 2013 and 2015, according to Rector. In it sits a plaque at the bottom.

“That was the original plaque for Robert Brooks,” said Rector. “The plaque used to sit adjacent to Quarters #1.”

Brooks was born Oct. 8, 1915, in Sadieville, Ky., to Black sharecroppers Ray and Adeline Brooks. His childhood, depending on which reports and stories are read, places him either in nearby Cincinnati with one of his two sisters by age 7 or not arriving there until he was fully grown. Mystery seems to surround him at every key moment of his life.

“We don’t have a lot of information about the personal life of Brooks, so we just have the basics to go on,” said Rector. “One account says he was born in McFarland and raised in Sadieville. Another says as an adult he moved to Cincinnati. The papers said he was born in Sadieville and lived there until he was 7. There’s conflicting information out there.”

One fact not in question about that time was that, for whatever reason, Brooks enlisted in the Army as a white man.

Unlike other Black men in America at that time, Brooks chose to breathe the same air as white men, train with them, eat with them, sleep in the same barracks, share jokes, maybe even enjoy a night or two on the town prior to them leaving post the next year.

While his skin tone suggested to them that he was a white man, his hair and voice inflection sometimes hinted otherwise, according to later accounts. Years later, some of those soldiers from his unit puzzled over Brooks’ decision to enter service under that guise.

“He lied about his race,” said Maurice “Jack” Wilson,” in a book titled, The Good War: An Oral History of World War II. “We was all white, see? And he lied to get in a white outfit.”

After Brooks enlisted in late 1940, he arrived at Fort Knox to attend tanker school as part of the Armored Force. Shortly afterward, he was assigned to Company D with plans to become a half-track and tank driver.

In the summer of 1941, Brooks and his unit traveled to Louisiana to learn more tactical maneuvers in a different environment. While there, they encountered obstacles; the ways that they adapted would soon change some of the procedures tankers used to successfully fight the Germans and Japanese.

While there, Brooks and the others also received orders to deploy to the Philippines, although it was discovered that Army leaders had already made that decision prior to their departure from Fort Knox.

“The entire battalion was loaded onto trucks and sent in a convoy to Louisiana while the tanks and wheeled vehicles were sent by train,” according to the Bataan Project. “They had no idea that they had already been selected for overseas duty.”

Another fact not in question was Brooks’ heroism, evident on the very first day of America’s entrance into World War II. According to an account by Morgan French, bombs began raining in the unit’s position. Rather than run and take cover, Brooks chose a different route.

Before Brooks could reach the half-track, a bomb, which turned out to be a dud, hit him, virtually splitting him in two: “He was killed instantly.”

Rector speculated that Brooks’ heroic death could be considered an act of mercy for him. A far worse fate lay ahead for members of Company D, 192nd.

“If Brooks had survived that day, he would have had additional challenges ahead of him with the Bataan Death March and Japanese POW camp,” said Rector. “Would he have survived either of those? His quick death did alleviate suffering that he would absolutely have experienced.”

Shortly after then Maj. Gen. Jacob Devers, commanding general of Fort Knox, made the decision to name the parade field after Brooks. A call to Brooks’ parents to invite them to the dedication revealed that he was in fact a Black man. It is said that didn’t change anything for Devers.

“In death there is no grade or rank,” said Devers at the Dec. 23, 1941, dedication ceremony, “and in this greatest Democracy the world has ever known, neither riches nor poverty, neither creed nor race, draws a line of demarcation in this hour of national crisis.”

The flag flew at half-mast during the ceremony, a rifle team fired a 21-gun salute and a bugle played taps in honor of Brooks’ ultimate sacrifice.

Rector said he has done some digging and can’t find a record of Brooks having received the Purple Heart, so Brooks’ only verifiable award was a posthumous promotion. And the naming of a parade field that has stood the test of time 80 years later.

“To have a parade field of a major Army installation named after you,” said Rector, “is a pretty big honor of itself.”